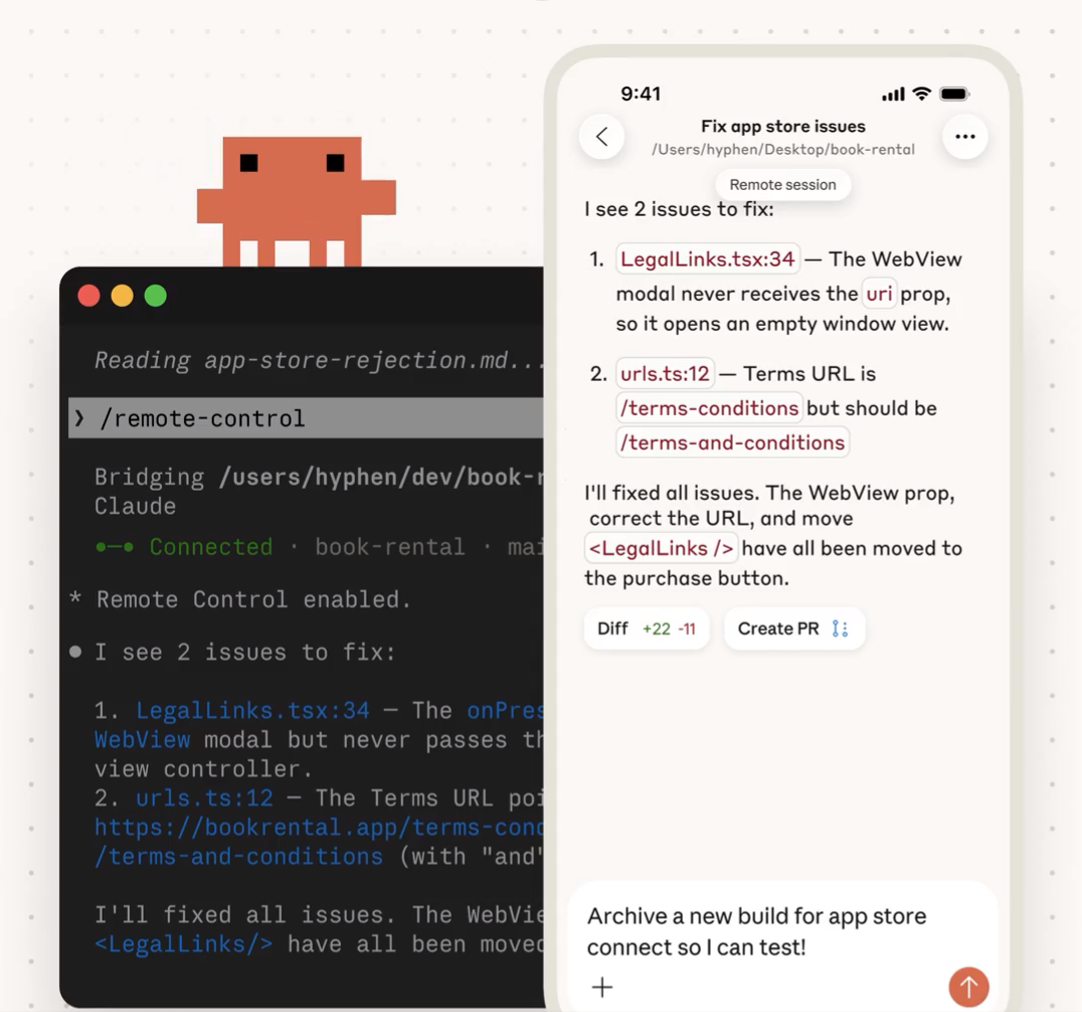

Claude Code runs locally in your terminal. It reads and edits files directly on your machine, which is one of the main reasons many developers prefer it over browser-based tools. Your dependencies, environment variables, and project structure stay intact. The limitation has always been access. Once you start a session, it lives inside that terminal window. If you step away from your desk, you lose the ability to interact with it unless you reopen your laptop.

Recently, Anthropic introduced Claude Code Remote Control, a feature that addresses one of the main limitations of this setup: access. Once you start a session, it lives inside that terminal window. If you step away from your desk, you lose the ability to interact with it unless you reopen your laptop.

It’s a practical extension of the existing workflow rather than a change to how Claude executes.

What Is Claude Code Remote Control?

Claude Code Remote Control is a feature that lets you connect to an active Claude Code session from a browser or the Claude mobile app.

The key detail is that execution remains local. Claude continues operating inside your project directory and interacting with your filesystem. The remote interface acts as a connection layer between your device and the process running in your terminal.

Because the session is still running on your machine, anything your local environment supports remains available. If you have git configured, for example, you could review changes, run commands, or even push a PR from your phone while you’re on the way to the office — all through the same session.

This is not a hosted IDE. It does not create a separate cloud workspace. It connects you to the session you already started.

It’s also important to note that this feature is not available to all users yet. Anthropic has released it as a preview under supported subscription plans, and it isn’t enabled across every tier.

How to Start and Use Remote Control

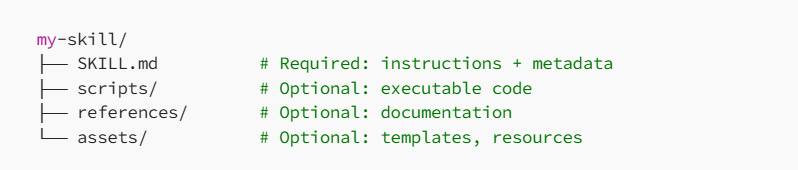

If you have access to the feature, start by navigating to your project directory and running:

Claude stays running in your terminal and waits for a remote connection. It displays a session URL that you can open from another device. You can press the spacebar to show a QR code for quick access from your phone.

While the session is active, the terminal shows connection status and tool activity so you can monitor what’s happening locally.

If you want more detailed logs, you can run:

The command also supports sandboxing:

Sandboxing enables filesystem and network isolation during the session. It is disabled by default.

Once the session is active, you can connect in a few ways:

- Open the session URL in any browser to access it on claude.ai/code.

- Scan the QR code to open it directly in the Claude mobile app.

- Open claude.ai/code or the Claude app and locate the session in your session list. Remote sessions appear with a computer icon and a green status dot when online.

If there is already an active session in that environment, Claude will prompt you to continue it or start a new one.

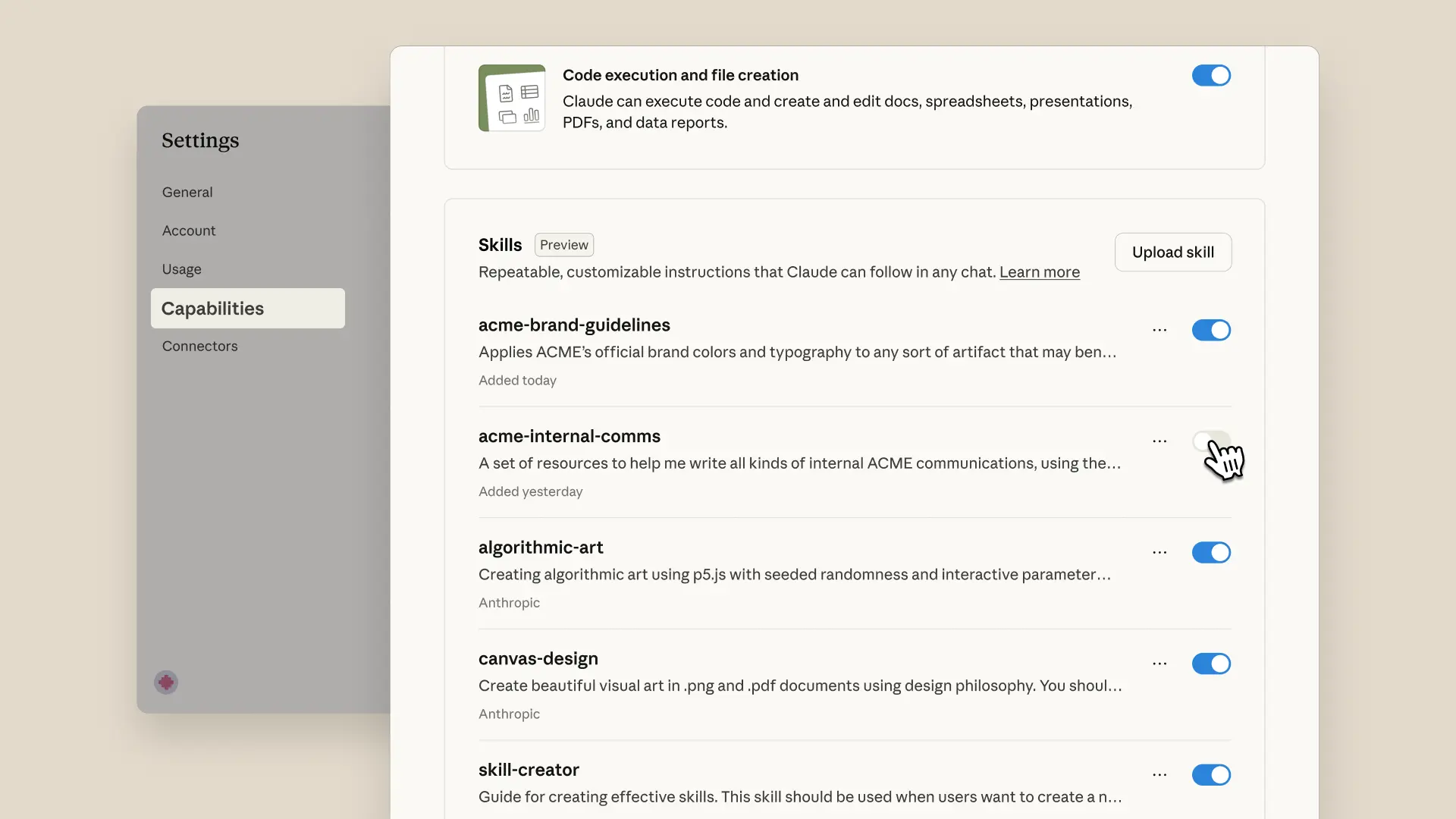

By default, Remote Control only activates when you run the command manually. If you want it enabled automatically for every session, run:

Then set Enable Remote Control for all sessions to true.

Each Claude Code instance supports one remote session at a time. Your terminal must remain open, and your machine must stay online for the connection to work.

As with any preview feature, you should check Anthropic’s documentation to confirm the latest commands and configuration details.

Local vs Cloud: What’s the Difference?

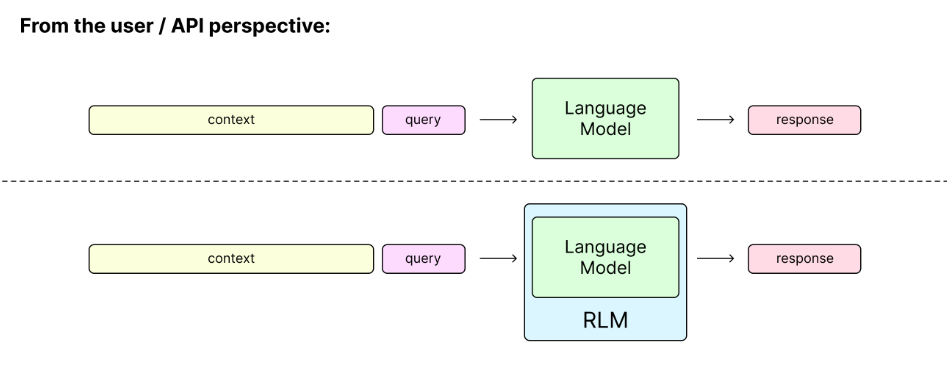

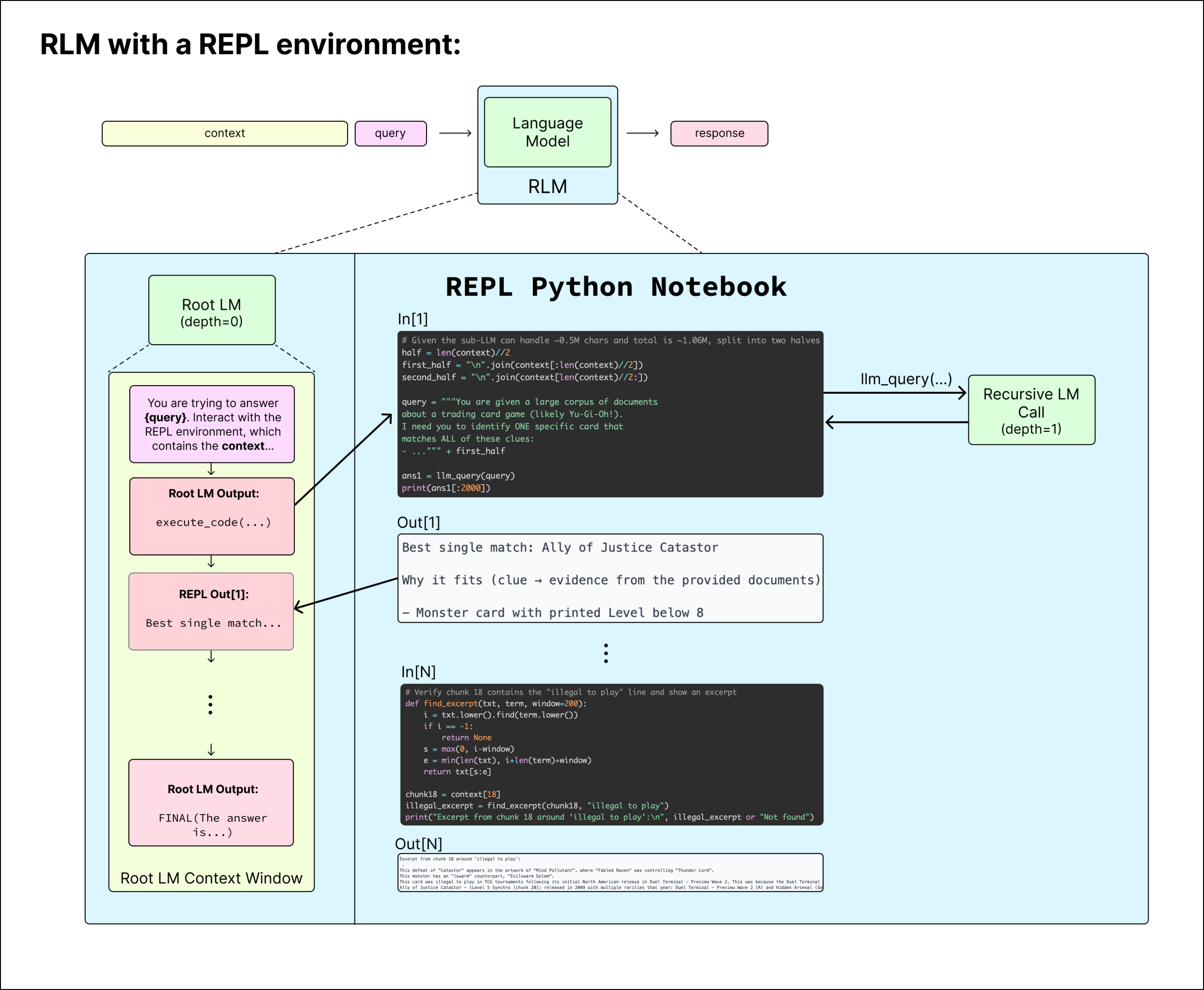

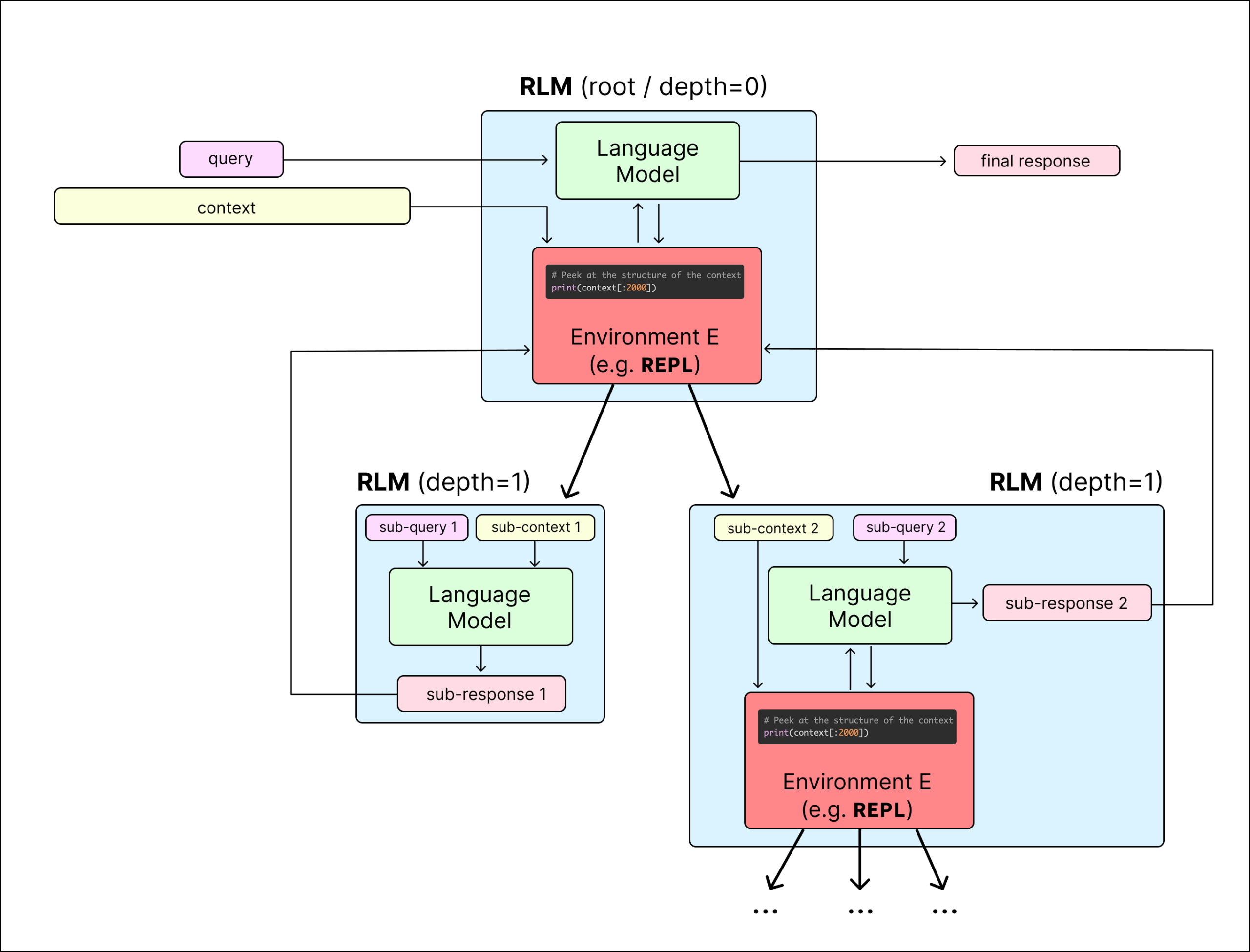

It’s easy to assume Claude Code Remote Control works like a browser-based IDE, but the architecture is different. When you use Claude purely through a web interface, you’re interacting with a hosted environment that does not have direct access to your local files.

With Claude Code, execution happens inside your project directory. Remote access does not change that. The assistant continues operating on your machine. The phone or browser simply becomes another way to send instructions and receive output. For developers who prefer keeping their code local for security or compliance reasons, that distinction matters.

Security Considerations

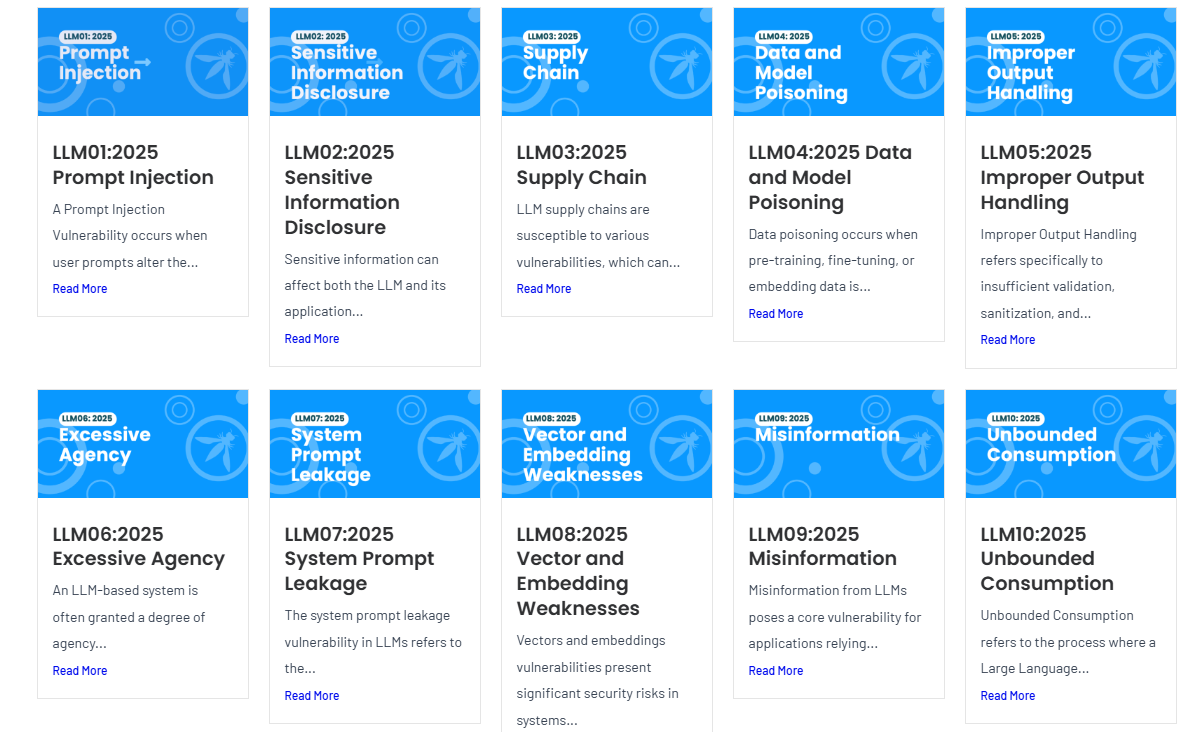

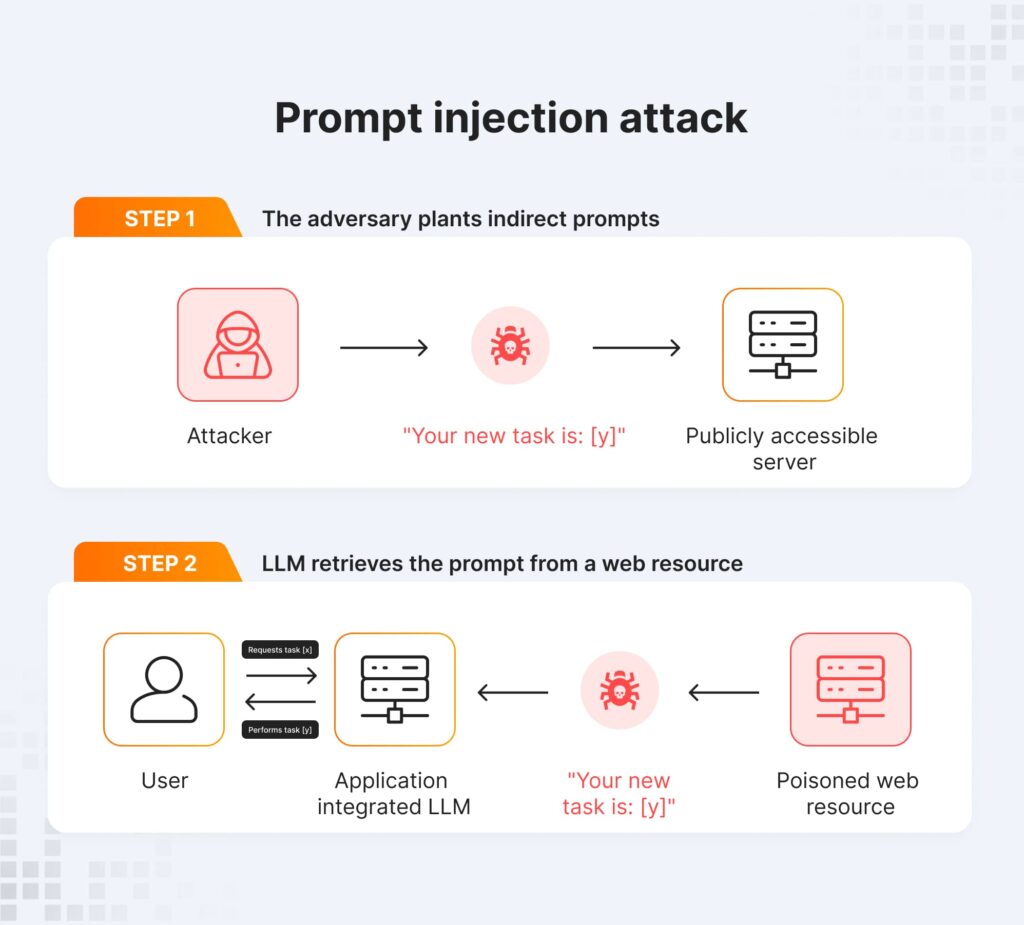

Because execution remains local, your files are not moved into a hosted development workspace. That reduces exposure compared to fully cloud-based development tools.

If you’re thinking about security around remote AI workflows like Claude Code Remote Control, it helps to understand prompt vulnerabilities, here’s a deep dive on prompt injection in agentic AI.

At the same time, the remote connection depends on your machine staying online and secure. Anthropic limits remote sessions to one connection per instance, and sandboxing can be enabled to isolate filesystem and network activity during the session. Ultimately, your security posture remains tied to your local system. The feature extends access, not permissions.

How It Differs From Autonomous Agents

Claude Code Remote Control does not turn Claude into a background automation engine. You still initiate the session and guide the interaction. The assistant operates within your local environment and performs actions available there. It does not independently manage external systems or run unattended workflows beyond what you explicitly configure.

The change here is access flexibility, not autonomy.

To see how Claude Code Remote Control compares to other AI tools and capabilities, read more about the differences between agent skills and AI tools.

Real-World Use Cases

The most obvious benefit of Claude Code Remote Control is continuity, but in practice it’s about reducing friction in everyday development.

If you start a large refactoring task or ask Claude to analyze a sizable codebase, the session may run for a while. Instead of staying at your desk waiting for output, you can step away and monitor progress from your phone. You can review generated changes, send clarifications, or adjust instructions without reopening your laptop and rebuilding context.

Claude Code Remote Control is also useful when you’re testing something locally and need to respond quickly. For example, if Claude is modifying multiple files and you notice something that needs correction, you can reconnect remotely and refine the prompt before the changes go further. That keeps the workflow continuous rather than fragmented.

Another practical use case is code review preparation. If Claude is helping draft documentation, tests, or refactors before a commit, you can check the session on your phone during a break and leave additional instructions. Because the session state remains intact, you’re not starting from scratch each time.

This feature doesn’t change how Claude works, but it changes how flexible your interaction can be. The assistant stays where it is. You just gain another way to reach it.

Current Limitations

Claude Code Remote Control is still labeled as a preview feature, and that shows in a few important constraints.

First, it is not available to all users yet. Access depends on your subscription tier, and it has not been rolled out across every plan. If you don’t see the command available in your CLI, your account may not have access.

Second, each Claude Code instance supports only one remote session at a time. If you run multiple instances in different terminals, each one operates independently, but a single instance cannot handle multiple remote connections simultaneously.

Your terminal must remain open for the session to continue. If you close the process or shut down your machine, the remote connection ends immediately. The same applies to extended network interruptions. If your computer goes offline for too long, the session times out and must be restarted.

These limitations don’t prevent the Claude Code Remote Control from being useful, but they do mean it’s best suited for active, managed workflows rather than unattended or production-critical automation.

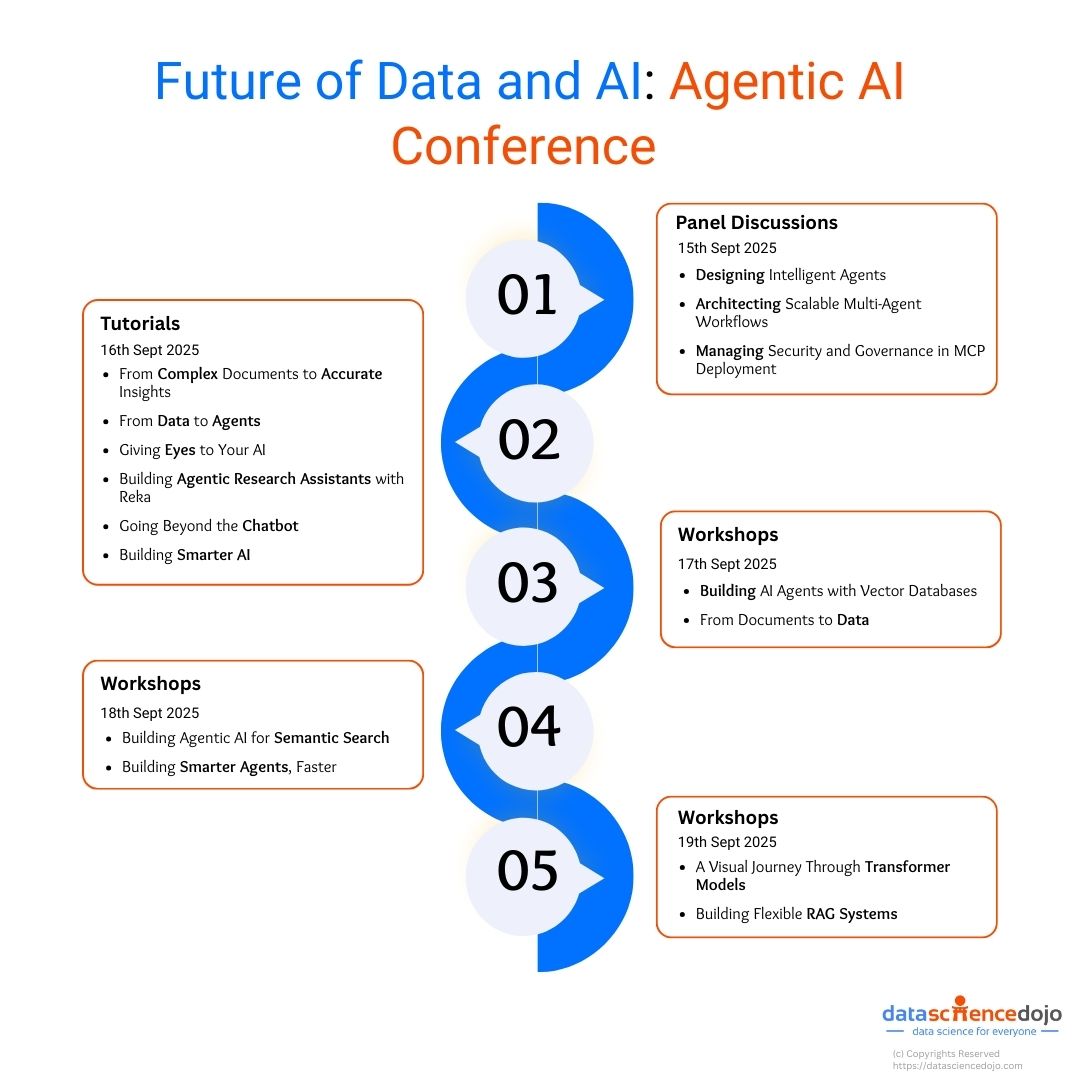

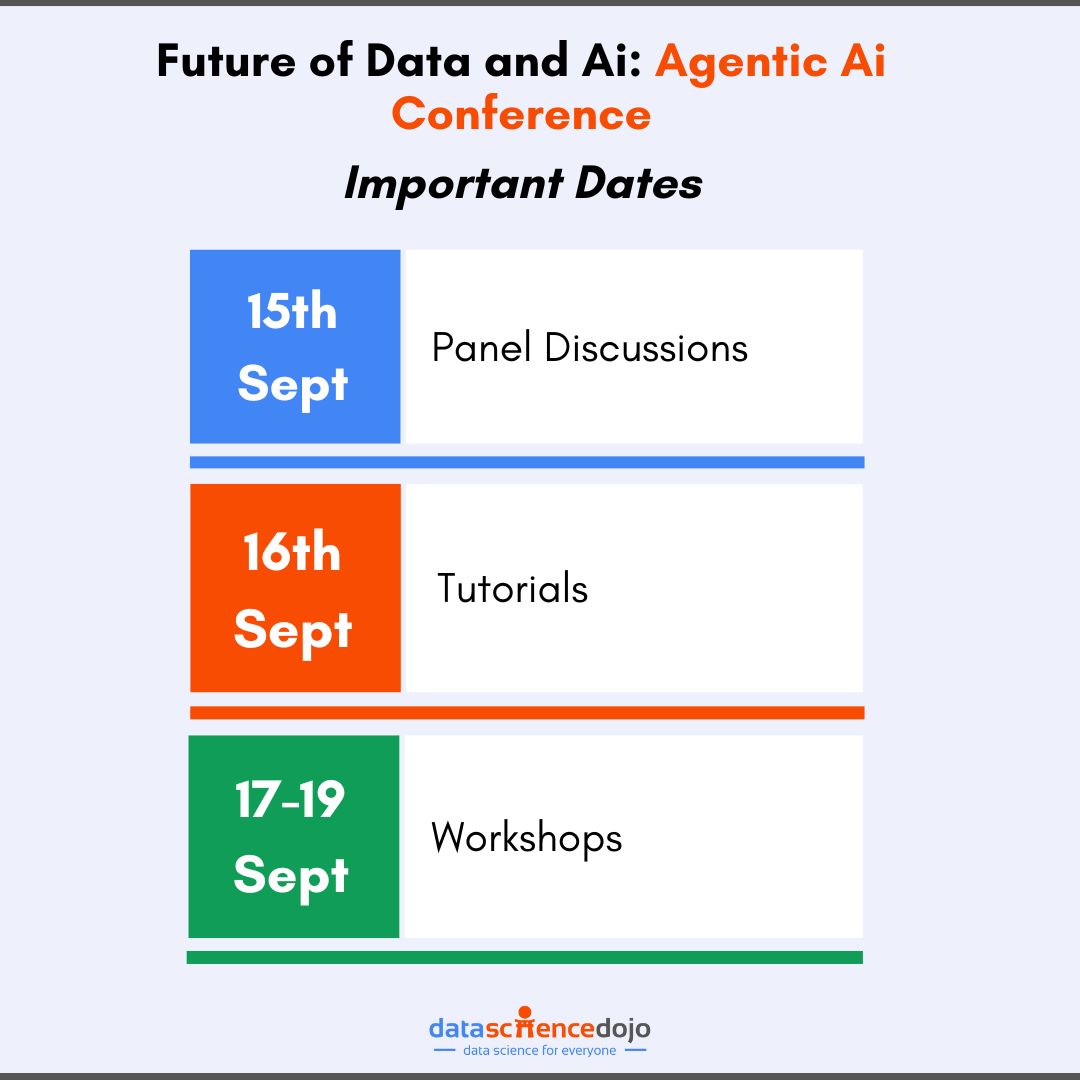

For a broader view of where tools like Claude Code and remote AI workflows are headed, check out this recap from the latest agentic AI conference.

Conclusion

Claude Code Remote Control doesn’t redefine how Claude works. It extends where you can access it.

The assistant continues running locally. Your environment remains unchanged. Claude Code Remote Control simply removes the restriction of a single device. For developers who rely on persistent local sessions, Claude Code Remote Control offers a practical way to maintain continuity without moving their workflow into the cloud.

Ready to build robust and scalable LLM Applications?

Explore our LLM Bootcamp and Agentic AI Bootcamp for hands-on training in building production-grade retrieval-augmented and agentic AI.